“Protection is not the problem – overfishing is the problem. The worst enemy of the fishing industry is themselves.” – National Geographic Explorer in Residence Dr. Enric Sala

The UN Decade of Ocean Science for Our Blue Planet

A Common Home Spotlight by ECo Faculty Network member Dr. Marisa O. Ensor

June 13, 2025

With the Mediterranean glittering in the background, thousands of scientists gathered in Port Lympia, Nice’s historic harbor on the French Riviera, to participate in the One Ocean Science Congress (June 3rd-6th, 2025). Our mission: to hammer out actionable recommendations to inform the global discussions at the 2025 UN Ocean Conference which took place the following week (June 9th-13th) in the same facilities. Co-chaired by France and Costa Rica, this high-level summit exhorted decision-makers and the broader community to confront the deepening ocean crisis and mitigate its cascading effects on biodiversity, food security, and climate resilience, among other urgent issues.

A poster describing how the One Ocean Science Congress centers science in the move towards a more sustainable ocean.

These two related initiatives are part of a constellation of global efforts organized under the aegis of the United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021-2030) (the “Ocean Decade”) proclaimed by the UN General Assembly in 2017 with the overarching theme “The Science We Need for the Ocean We Want.” Building on the best available science and recent achievements in global ocean governance, the Ocean Decade seeks to catalyze transformative action and deliver positive change across all geographies, stake- and rights-holders, sectors, disciplines, and knowledge systems to protect our global marine ecosystem. Recent events in Nice are meant to advance such lofty goals.

The “Ocean Decade”

The United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development provides a convening framework for a wide range of stakeholders (e.g., the UN system, intergovernmental organizations, international financial institutions, civil society organizations, the scientific community, the private sector, Indigenous peoples and local communities, etc.) working together to develop the scientific knowledge and the partnerships needed to “accelerate and harness advances in ocean science.” The UN General Assembly mandated UNESCO’s Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC) – the body responsible for supporting global ocean science and services–to coordinate the preparations and implementation of the Ocean Decade.

The ultimate goal is to deliver science-based solutions – with “science” understood inclusively, integrating diverse knowledge systems such and Indigenous and local knowledge (ILK) – to achieve the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development which includes Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 14 Life Below Water: Conserve and Sustainably Use the Oceans, Seas, and Marine Resources.

The Ocean Decade has proclaimed 10 Ocean Decade Challenges, which articulate the most immediate priorities towards achieving its goals and SDG 14:

- Understand and beat marine pollution.

- Protect and restore ecosystems and biodiversity.

- Sustainably nourish the global population.

- Develop a sustainable, resilient, and equitable ocean economy.

- Unlock ocean-based solutions to climate change.

- Increase community resilience to ocean and coastal risks.

- Sustainably expand the Global Ocean Observing System.

- Create a digital representation of the ocean.

- Skills, knowledge, technology, and participation for all.

- Restore humanity’s relationship with the ocean.

UN Ocean Conferences, like the most recent one in Nice, France, serve as platforms to mobilize action and partnerships to address these 10 challenges. The 2025 UN Ocean Conference – often abbreviated as UNOC 3 – was the third UN Ocean Conference. Previous conferences were held in New York in (UNOC 1, co-hosted with Fiji and Sweden in 2017), and Lisbon (UNOC 2, co-hosted by Portugal and Kenya in 2022). These conferences shine a global spotlight on the ocean and are the highest-level global fora to focus on ocean protection and sustainable use.

Protecting Our Blue Planet’s Life Support System

Without the ocean, life on our planet would be impossible. The ocean covers more than 70 percent of the Earth’s surface and is home to 94 percent of all life on Earth. It produces at least 50 percent of the planet’s oxygen, plays a core role in regulating the climatic system, and provides food to more than a billion people while supporting the livelihoods of millions more. Conservation International estimates that there are 600 million people worldwide who depend on fisheries and aquaculture for their livelihoods.

Yet, this vast, life-sustaining ecosystem faces growing threats, including overfishing, climate change, pollution, and deep-sea mining. Half of coral reefs have already been destroyed, 90 percent of big fish populations have been depleted, and an estimated 60 percent of marine ecosystems have been degraded or are being unsustainably used. Decades of overfishing, habitat destruction, pollution, and climate change impacts are pushing marine ecosystems toward collapse. Since 1950, with the onset of industrialized fisheries, the entire fisheries resource base has been reduced to less than 10 per cent worldwide. Emerging threats like deep-sea mining risk further irreversible harm to ecosystems we still barely understand.

A recent report by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) titled Review of the State of World Marine Fishery Resources 2025, offers a nuanced view of global fisheries. While 77 percent of globally consumed fish come from sustainable sources, largely due to effective fisheries management, over one-third of marine fish stocks remain overexploited. Regional differences are stark: sustainability exceeds 90 percent in areas like the Pacific coast of North America and the Antarctic but drops significantly in regions such as northwest Africa and the Mediterranean, where overfishing is widespread. A significant finding of the report is that recovery is possible – tuna stocks, once critically threatened, now show strong signs of rebound, with 87 percent sustainably fished. A reduction in harmful fishing activity in overexploited regions suggests that recent policy interventions may be yielding positive results. In the most extensive evaluation of its kind to date, another recently released study demonstrates that marine protected areas (MPAs – designated oceanic conservation zones akin to national parks) generate significant economic advantages for both the fishing and tourism sectors.

Yet, today, only 8 percent of the ocean is partially protected – and less than 3 percent is fully protected from extractive activities like commercial fishing and mining, according to the Marine Protection Atlas. Working to reverse this situation, world-renowned marine biologist and National Geographic Explorer in Residence, Enric Sala launched the Pristine Seas project in 2008 to explore and help inspire the protection of the ocean from unsustainable human practices. As Dr. Sala noted at the 2025 UN Ocean Conference, “Protection is not the problem – overfishing is the problem. The worst enemy of the fishing industry is themselves.” Bringing together a team of scientists, conservationists, filmmakers, and policy experts, and working with local communities and Indigenous peoples, Pristine Seas has helped protect 6.9 million square kilometers of ocean habitat. These include areas that have been degraded by overfishing and other exploitative activities, with the goal of allowing them to bounce back.

Fulfilling Our Responsibility to the Future

The recent One Ocean Science Congress and the UN Ocean Conference constitute key milestones for advancing ocean sustainability through science-based policy, innovation, and international cooperation. The congress resulted in a document that outlines 10 specific actions and five cross-cutting recommendations to ensure that science remains at the heart of efforts to secure a sustainable future for the ocean and humanity. Its authors underscore that strengthening collaboration between scientists and policymakers, while also integrating diverse knowledge systems, including Indigenous and local perspectives, is essential to advancing science-based policies that ensure long-term ocean sustainability, foster inclusivity and public engagement, and drive innovation through interdisciplinary research. My own contribution exploring knowledge systems integration, maritime heritage, and culture-based climate action, drawing on my fieldwork among coastal communities off the coast of Senegal helps to support Action 1– Inspire Responsibility and Respect for the Ocean, Integrating Across Knowledge Systems.

Similarly, the conference issued a declaration called the Nice Ocean Action Plan, a two-part framework that comprises a political declaration and over 800 voluntary commitments by governments, scientists, UN agencies, and civil society. Commending the leadership of Small Island Developing States (SIDS) for their role in addressing sea level rise, the declaration also expressed concern for the high and rapidly increasing levels of plastic pollution and its negative impacts on SIDS and the overall environment. Furthermore, the declaration called on States to promote awareness and education to inform the public about the importance of a healthy ocean and resilient marine ecosystems.

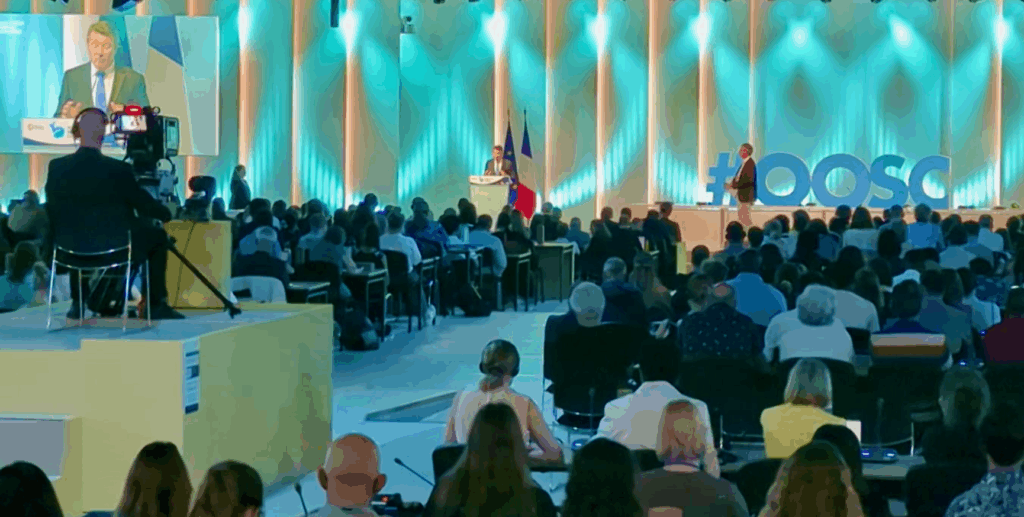

Christian Estrosi, Mayor of Nice, opening the One Ocean Science Congress. The room is bathed in blue-green light to resemble the ocean.

This declaration was designed to align with the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework – the 2022 agreement to protect 30 percent of the planet’s land and ocean by 2030. Another one of the conference’s main objectives was to accelerate progress on the Agreement on Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ Agreement), adopted in 2023 after protracted negotiations that lasted almost two decades. Also known as the High Seas Treaty, the BBNJ agreement requires sixty ratifications to enter into force. Recognizing the negative impact of unregulated activity on the ocean, 20 countries ratified the accord during the Ocean Conference, bringing the total number as of the conference’s conclusion (13 June) to 51, still nine short of what is needed.

Calls to halt deep-sea mining were also heard at the conference, with 37 countries now supporting a precautionary pause or outright ban, and more than 20 new marine protected areas being announced — hopeful signs of political will to protect fragile ecosystems. “Protecting the ocean is beginning to become fashionable,” said Sylvia Earle, a marine biologist and oceanographer who served as chief scientist of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in the 1990s. As a National Geographic Explorer at Large, and the founder, chairperson, and president of the Mission Blue foundation, Dr. Earle – affectionately called “her deepness” – draws on science and storytelling to inspire action to explore and protect the ocean. Additionally, representatives from SIDS pushed for stronger language on loss and damage – harms inflicted by climate change that go beyond what people can adapt to. “You cannot have an ocean declaration without SIDS,” one delegate warned.

The high-level events recently held in Nice culminated in a shared call to expand marine protection, curb pollution, regulate the high seas, and unlock financing for vulnerable coastal and island nations. As coral reefs bleach, fish stocks collapse, and sea temperatures break records, it is up to us – scientists, governments, businesses, Indigenous and local peoples, individuals, and the global community – to work together to translate Ocean Decade commitments into meaningful actions that will ensure a thriving and healthy ocean for current and future generations.