1 in 5 Butterflies Have Vanished in the U.S.—New Study Sounds the Alarm

The Most Comprehensive Butterfly Study to Date Reveals a Devastating 22% Population Decline in Just 20 Years

March 6, 2025

A sweeping new study published in Science tallies butterfly data from more than 76,000 surveys across the continental United States. The results: between 2000 and 2020, total butterfly abundance fell by 22% across 554 species. That means that, on average, for every five butterflies in the contiguous U.S. in 2000, only four remained by 2020.

“This is one of the largest-scale and most integrated analyses on population trajectories of any insect community,” said Leslie Ries, director of the Lab of Butterfly Informatics at Georgetown University’s College of Arts & Sciences and a co-author of the study. “Its main importance is to keep building evidence about insect declines—whether certain groups or all groups are being affected. For butterflies in America north of Mexico, the story is saddeningly similar, even many common species that have traditionally thrived in human-impacted environments seem to be declining.”

Ries, along with Georgetown co-authors Elise Larsen and Naresh Neupane, played a pivotal role in this study by providing statistical expertise, taxonomic insights, and supporting the online web systems that make these data easier to collect, manage, and share. Their lab has spent over a decade developing the North American Butterfly Monitoring Network and PollardBase, used by 16 of the 19 regional butterfly community monitoring programs contributing data to this research. These platforms unify regional efforts, enable large-scale tracking, and allow researchers to assess population trends at unprecedented scales.

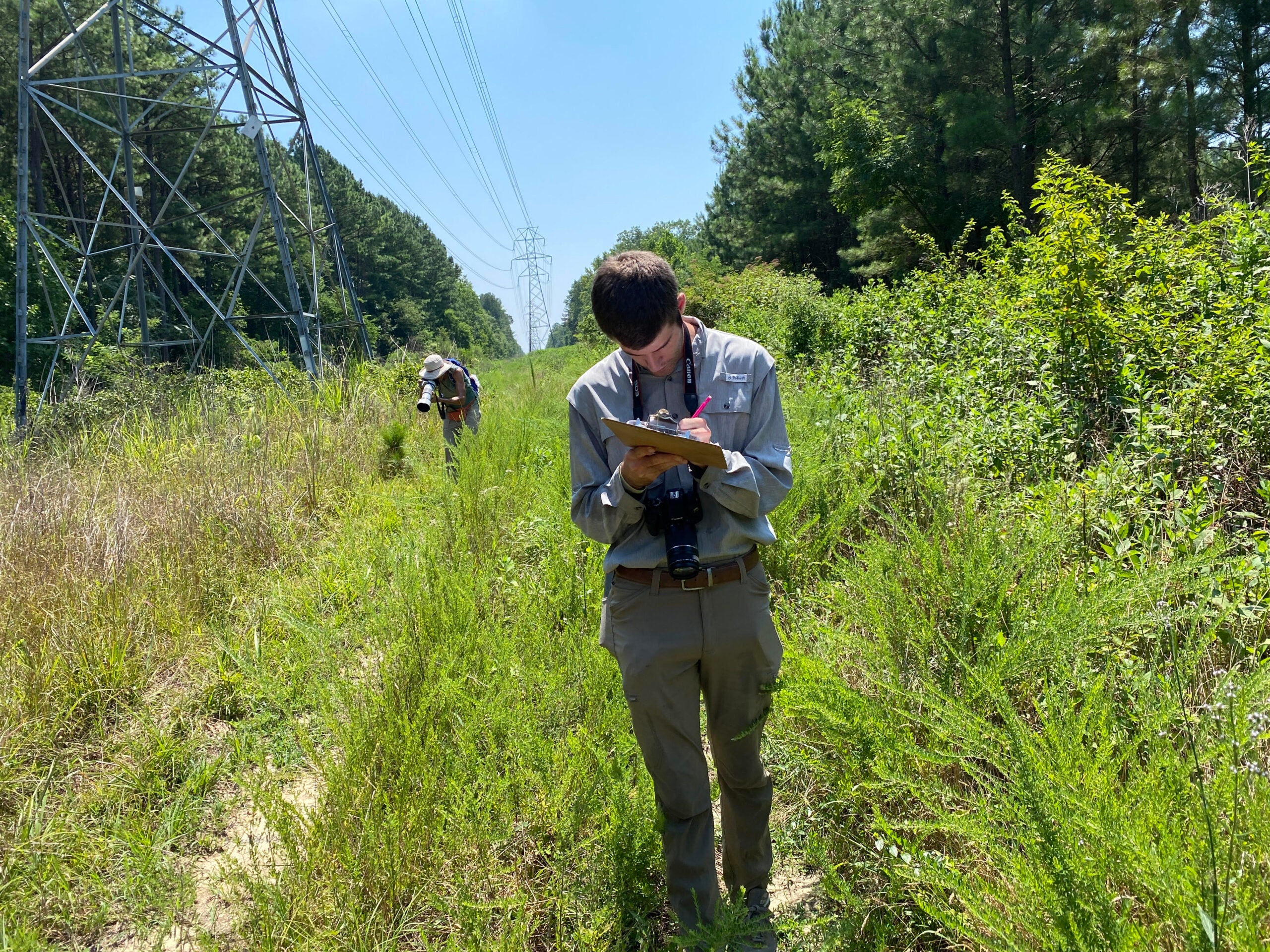

Every year, thousands of volunteers take to the field to collect butterfly data, forming the backbone of this research. These naturalists, educators, and activists are part of a growing “participatory science” movement. While amateur naturalists have long contributed to biodiversity studies, today’s organized butterfly monitoring programs are expanding rapidly, increasing both data volume and accessibility.

“Butterfly monitoring this widespread wouldn’t be possible without dedicated volunteers who contribute their time and expertise,” said Ries. “Our goal is to expand the scale of data collection, engage more participants, and ensure the data is accessible to scientists and policymakers. The beauty of participatory science is that it allows us to collect information at an unprecedented scale while fostering a deep connection between people and nature.”

These volunteer-driven efforts allow researchers to track more than just population numbers. They analyze changes in species distribution, track migration timing, detect unusual population fluctuations, and study ecological dynamics across local, regional, and continental levels. These insights are critical for understanding long-term environmental shifts and shaping conservation strategies.

The study examined surveys that counted over 12.6 million butterflies from 35 programs. Populations declined by an average of 1.3% each year, with 107 species losing over half their numbers in the 20-years of the study.

Species in the study were 13 times more likely to be clearly declining than clearly increasing. The study mirrors findings from other biodiversity studies, including a 2019 co-authored by Georgetown’s Peter Marra, which revealed that North America has lost nearly 3 billion birds.

Beyond their beauty, butterflies are critical to ecosystems and the people who depend on them. People often think of bees first, but butterflies also pollinate wildflowers and many crops. They play a significant role in nutrient cycling and serve as a food source for birds and other wildlife. Their populations also provide a critical early warning system for broader biodiversity changes, as butterflies respond quickly to environmental disruptions.

While the study highlights a crisis, it also points to solutions. Research co-authored by Ries found that pesticides, especially neonicotinoids, are strongly linked to butterfly declines. The widespread use of insecticides has devastated pollinator populations, but reducing their use is an actionable step toward recovery.

“We have strong evidence that pesticides, particularly neonicotinoids, are a major driver of butterfly declines,” Ries said. “Reducing unnecessary insecticide use, particularly in agriculture, and restoring underutilized cropland to natural habitats could provide immediate benefits to butterflies and other pollinators.” Study co-author Nick Haddad, a professor of integrative biology at MSU adds, “A lot of insecticide use lacks strategy and results in overuse. Some 20 percent of cropland suffers from poor yields. Creating policies that return under-producing land to nature could help the butterflies to rally.”

“This is the definitive study of butterflies in the U.S.,” said Collin Edwards, the study’s lead author. “For those who were not already aware of insect declines, this should be a wake-up call. We urgently need both local- and national-scale conservation efforts to support butterflies and other insects. We have never had as clear and compelling a picture of butterfly declines as we do now.”

Larsen emphasizes there is more research yet to be done. “We need to understand what is causing these population declines, especially the drivers that local conservation communities can affect. What conservation efforts are most important to protecting these populations and species locally, so they are better able to adapt to new stressors?”

This research underscores the importance of continued investment in biodiversity monitoring and conservation strategies to ensure that future generations do not inherit a world without butterflies.

The Ries Lab of Butterfly Informatics at Georgetown University studies large-scale patterns of insects, mostly butterflies, using a combination of laboratory and data-intensive approaches.

Media Contact:

Justine Bowe

The Earth Commons, Georgetown University’s Institute for Environment & Sustainability

justine.bowe@georgetown.edu

High-resolution images available for download here.

End of carousel collection.