Writing Climate Interviews: How Literature Can Shape the Fight for a Livable Future

Can storytelling shift the climate narrative and spark real change? Ahead of Georgetown’s Writing Climate Symposium, we speak with the featured writers, poets, and activists leading the conversation on how literature can bridge the gap between science and society, amplify frontline voices, and reshape our relationship with the planet.

There is no shortage of headlines fighting for attention in today’s state of affairs. In the background, with or without media attention, the ecological clock continues to tick and action on all scales (international, national, and local) continues to meet obstacles at every turn. This has led many climate activists to the conclusion that a cultural shift is required in order for real change to occur. That’s why, according to Brad Adams, Executive Director of Climate Rights International, “We need the cultural community to help lead the way.”

Adams knows a cultural shift is possible because of the role literature played in shaping his own trajectory as a climate activist. He recalls sending poignant books and articles between friends and fellow activists ultimately leading to his work in founding Climate Rights International which works to document climate-change-related human rights abuses and create partners within powerful governments and institutions to take action on the abuses.

Climate stories don’t have to be overtly didactic or apocalyptic; they can be subtle, personal, and even humorous. Most importantly, remember that storytelling is an act of hope.

– Amitav Ghosh | RSVP Now to Writing Climate

At the end of this month, Climate Rights International joins the Lannan Center for Poetics and Social Practice, the Earth Commons , Climate Rights International , and Georgetown Humanities Initiative in hosting this year’s Lannan Symposium: Writing Climate. In its own words, the symposium seeks to prompt discussion on how “we imagine a fundamental shift in thinking about human existence” and “what can we do as individuals, as writers, activists, and scientists, to forestall and ameliorate the coming disasters”—essentially, how the cultural community can lead the way.

Despite literature’s personal impact on Adams, he knows that this conversation is essential because “climate advocates continue to fail to connect with people outside of the existing affinity group.” The original 1970s environmental movement was largely touted as a lawyer-led movement and even mainstream climate narratives today focus on the scientific and technical aspects of climate change, often minimizing the role of Indigenous and other BIPOC movement leaders and their stories. Moving the narrative to one focused on the real ways climate change is and can impact humans is necessary to shift how climate change is viewed in the public mind. Adams sees “all creatives across disciplines as essential ingredients to push the cultural narrative towards a mindset ready for progress.”

Hosted by the Lannan Center, the Earth Commons , Climate Rights International , and Georgetown Humanities Initiative , the “Writing Climate” symposium will explore the intersection of literature, science, and activism around climate change. RSVP Now

That is why, in organizing the symposium, the collaborators sought artists in all forms—poets that weave Indigenous modes of being with our current disaster, novelists who process our current condition by imagining the stories of the future, journalists who document the climate stories happening now, and, even, Georgetown students who are finding new ways to tell climate stories and bring the public into the fold.

All of their work demonstrates the power of the intersection between arts and activism. Meet some of the visionary voices below and be sure to join them in conversation March 25th-27th on campus.

Omar El Akkad

Omar El Akkad is an author and journalist. He was born in Egypt, grew up in Qatar, moved to Canada as a teenager, lives in the United States, and is currently a Visiting Fellow at Georgetown University-Qatar. His books have been translated into 13 languages.

What do you feel is the role of literature/writing in the climate movement?

I think literature is incompatible with a corseted imagination. It’s not the obligation of the writer to change anyone’s mind, to convince them of any one position. But we do have an obligation to approach the world from a storytelling perspective unincumbered by the idea that all of this – a world coming slowly undone by capitalism and colonialism and the intertwined climate nightmare – is the best we can do.

What advice do you have for students and/or young writers that want to tell climate stories?

You are entering a literary tradition that, relatively speaking, is in its infancy. You don’t have the luxury of centuries of canon to rest your work on, at least in much of the European tradition, and you have every right to be angry about what’s been done to this world, the many ways in which your future has been mortgaged for someone else’s present-day convenience. Don’t let any of this stop you. Write your stories on your own terms, experiment with forms and styles, and build the bedrock on which future writers’ stories can more easily stand.

[Young writers] don’t have the luxury of centuries of canon to rest your work on…and [they] have every right to be angry about what’s been done to this world.

Omar El Akkad

If you distilled your work into one message, what would it be?

I have no idea. I write against the privilege of looking away, I try to imagine how people might behave, how they might be forced to change, were they not so easily able to look away. But you sort of lose your mind, as a writer, trying to dictate to the reader what the story should be, or how it should be read.

End of carousel collection.

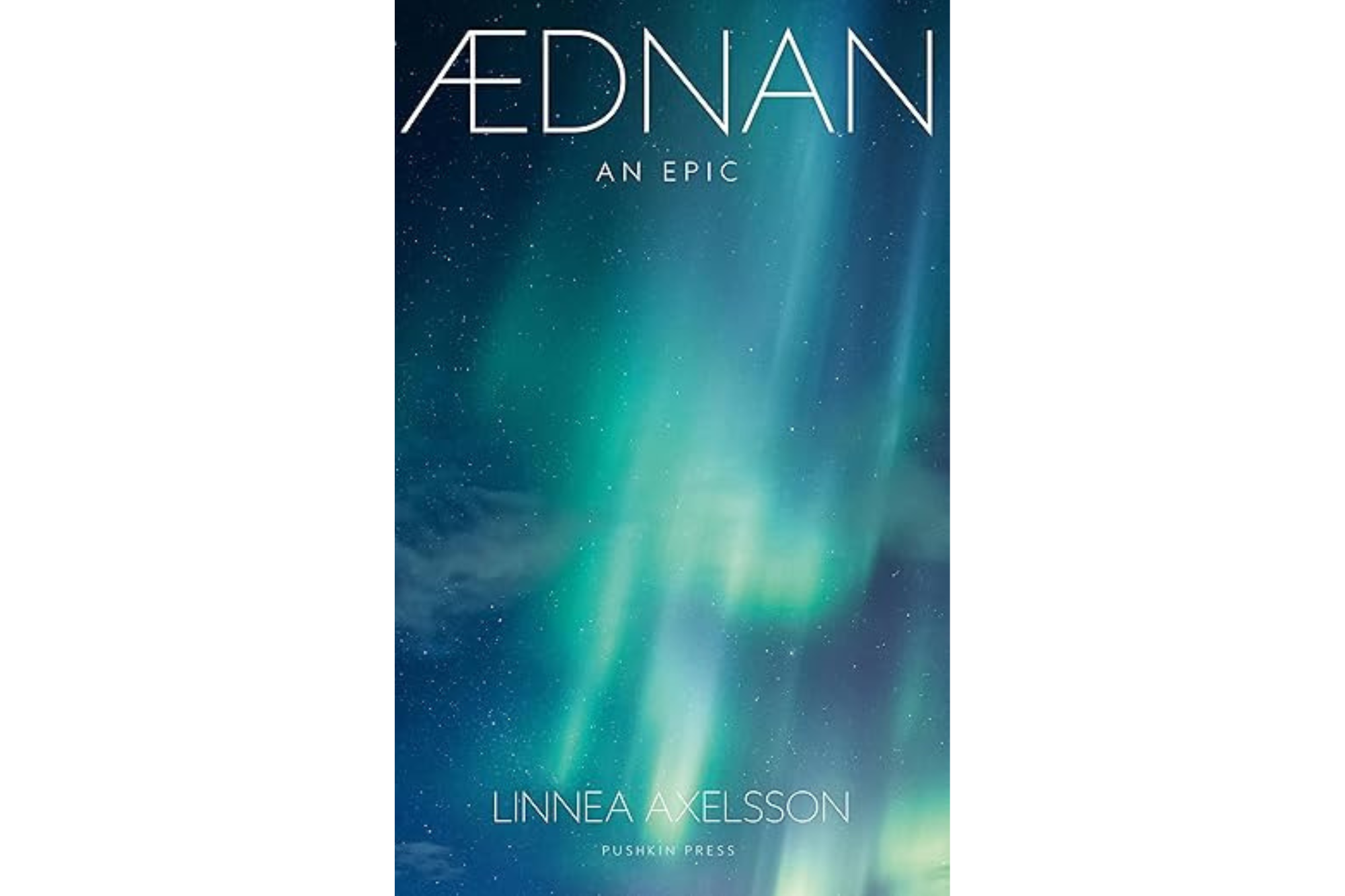

Linnea Axelsson

Linnea Axelsson is a Sámi-Swedish writer, born in the province of North Bothnia in Sweden. In 2009, she earned a PhD in Art History from Umeå University. In 2018, she was awarded the August Prize for Ædnan. She lives in Stockholm, Sweden.

What is your climate story? How did you come to this work?

I don’t know that I myself would phrase it in the manner of me having a climate story. Rather, from my point of view human is part of nature, and nature is within human. They are part of a singular cosmology. With that rootedness, the people I imagine when I write are intertwined with climate – the climate of a specific place, of course connected to climate as a whole, since it knows no borders. And whatever dramas take place in climate, on some level take place in human life.

“Language allows for me to engage in all different kinds of questions, and if nature and climate are amongst them it is probably because of the relationship between human and earth.”

Linnea Axelsson

How did you come to your form of writing? How does it allow you to engage in questions of the climate?

I came to poetry and fiction I guess through how I respond to and engage with language – what appeals to me aestethically and imaginatively. Language allows for me to engage in all different kinds of questions, and if nature and climate are amongst them, it is probably because of the relationship between human and earth.

What advice do you have for students and/or young writers that want to tell climate stories?

Try and listen to whatever material they got, making an effort to understand what it carries with it. And then see if this is something that wants to be a piece of fiction or rather an essay, and figure out how to best be of service to the language of that text.

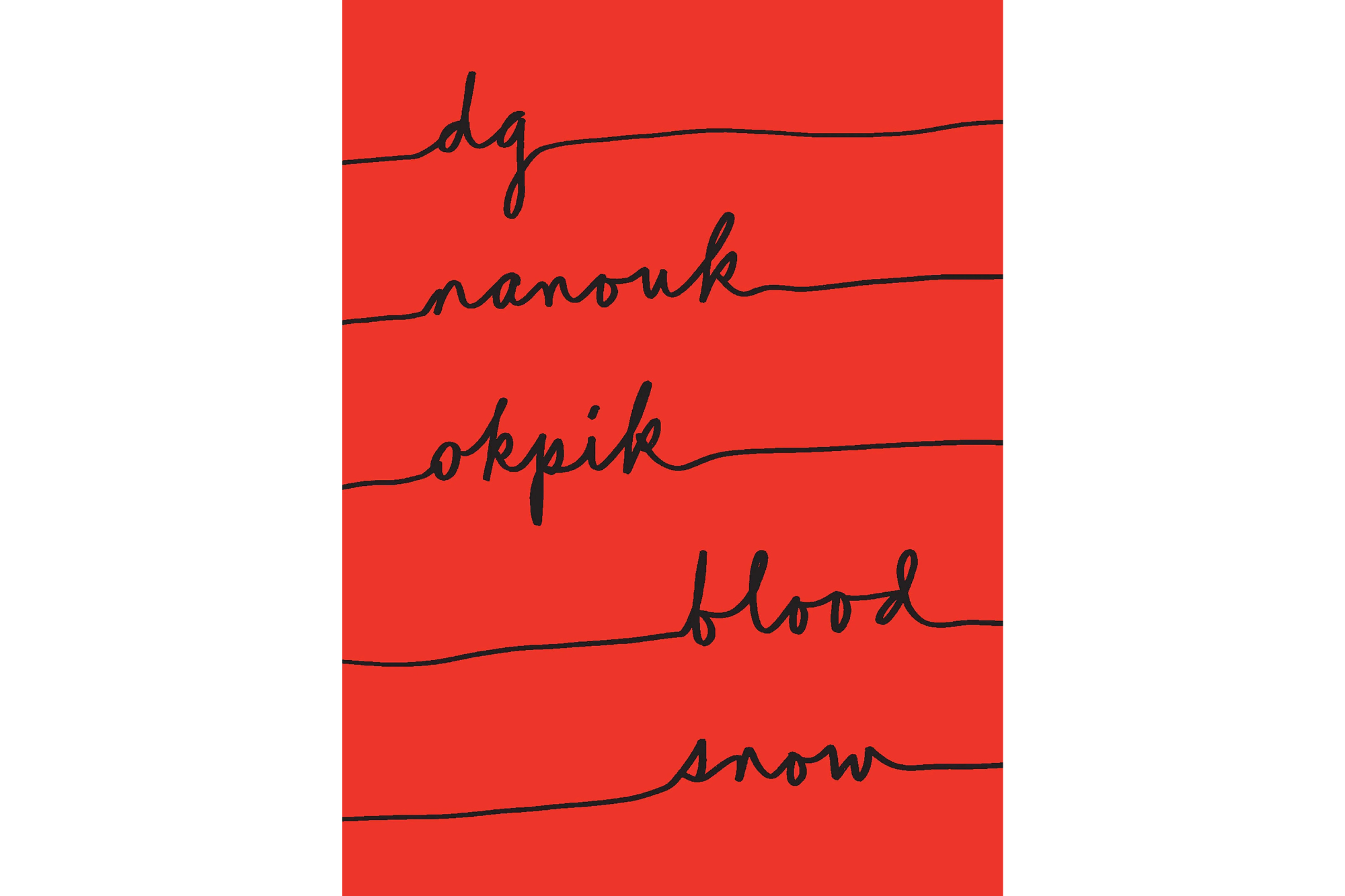

dg nanouk okpik

dg nanouk okpik was born in and spent much of her life in Anchorage, Alaska. She attended Salish Kootenai College, the Institute of American Indian Arts, and Stonecoast at the University of Southern Maine. okpik has won the Truman Capote Literary Trust Award, the May Sarton Award, and an American Book Award.

What is your climate story? How did you come to this work?

I came to this work at age 12, when I read The Autobiography of Malcolm X. He learned to read and write while incarcerated by reading the dictionary, word by word, copying the word down and learning the definition. So, I came to my work using the dictionary and by experiencing the land, and the climate, of Alaska, my home. I’ve lived catching minnows in a trap. I’ve lived moose hunting. I’ve touched the skin of a whale going by my dad’s umiak, his boat. I’ve caught salmon and held their breathing hearts in my hand. I grew up doing that.

I was adopted so I came to my people’s language, Inupiaq, later in life. So, to write, I learn the specificity of the language of Inupiaq, and then I turn Inupiaq imagery into English, then I transcribe it four times, or translate it from English to Inupiaq, and then I find a middle ground. I marry the two, if that makes sense, in a way that is well thought out, but is also spontaneous– and I can make it new. The metaphor it becomes, I use in my work.

I’m rewriting tundra. I’m rewriting a new path in English.

dg nanouk okpik

What do you feel is the role of literature/writing in the climate movement?

I do not think I am an eco-poet. I’m a poet. If you read my writing, Alaska is in the mesh and bones of the work, and that climate automatically comes out in me, because I’m Native. Natives aren’t environmentalists, they just know the land and they know the spirits. They know the ceremonies and the stories, the poetry and song that go with it. In our ceremonies, we dance and sing poetry. When you hear the cadence in my writing, it is my Inupiaq drum at home. So, poetry is an active thing. We live our poetry daily. Oral traditions and stories have been passed down for hundreds and hundreds of years– it is not written. So, I’m rewriting tundra. I’m rewriting a new path in English.

I tend to write environmental ideas because that’s what’s going on in Alaska. Barges go up and down the Arctic pass carrying thousands and thousands of tons of tons of waste for nuclear facilities through that waterway, which is only 60 miles wide. When they burn the sludge on the barges, they dump it into the Artic and it permeates the waterways. Now it’s coming up in the tundra along with the oceans and the fish. There is mass destruction. Animals dying. Climate change. So, that is what I write about–the issues impacting my home. My writing is native derivative, not this idea, this word put on me, eco-poet. Even though I am gracious to own it, you know, you don’t say a bear’s a bear and ask him to be a bear.

I’m an Inuit, I’m an Inupiq, I’m American, and I’m a poet–I am an Inuit contemporary woman facing multiplicity as background.

What advice do you have for students and/or young writers that want to tell climate stories?

Buy a dictionary and The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics.

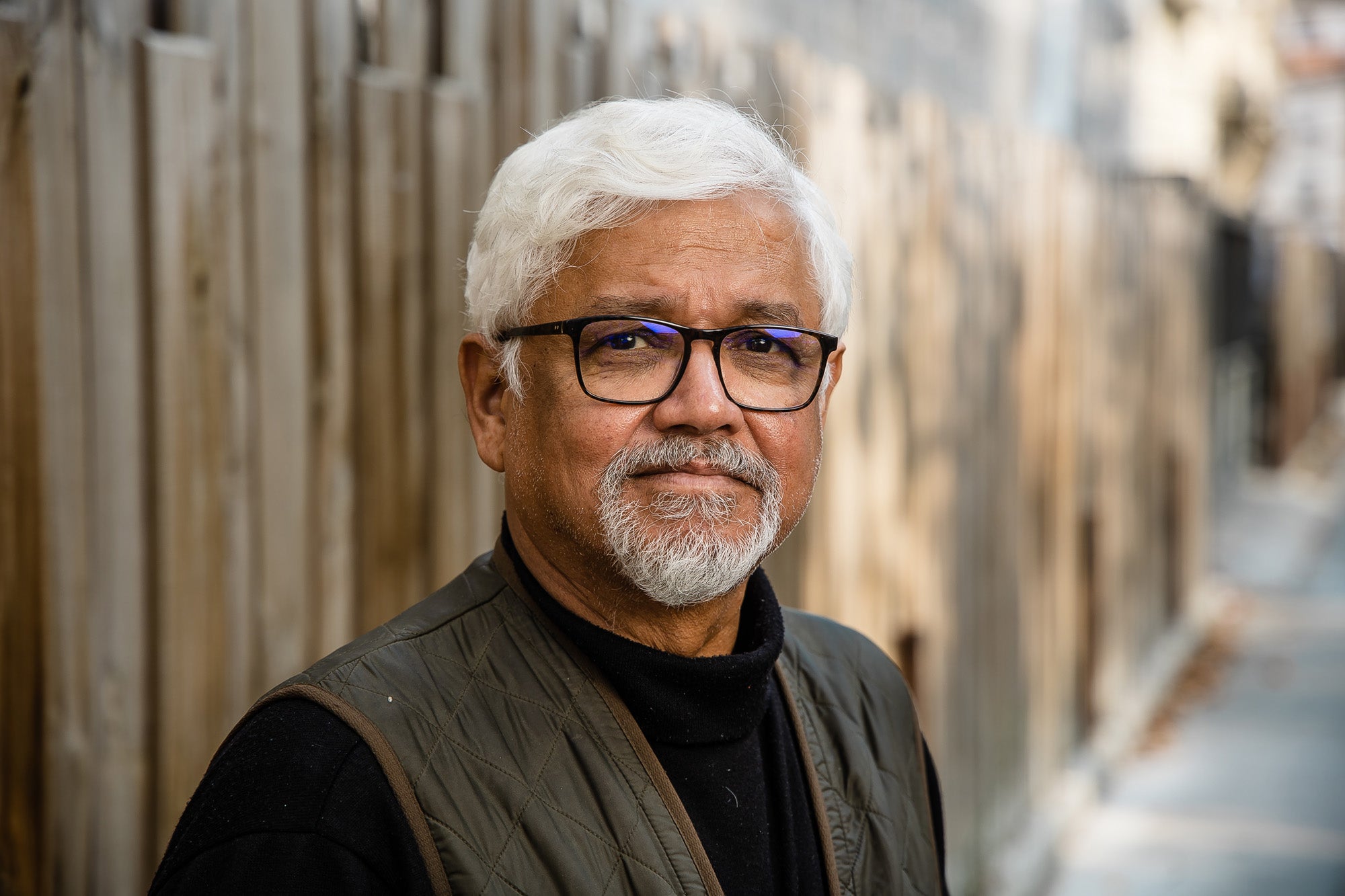

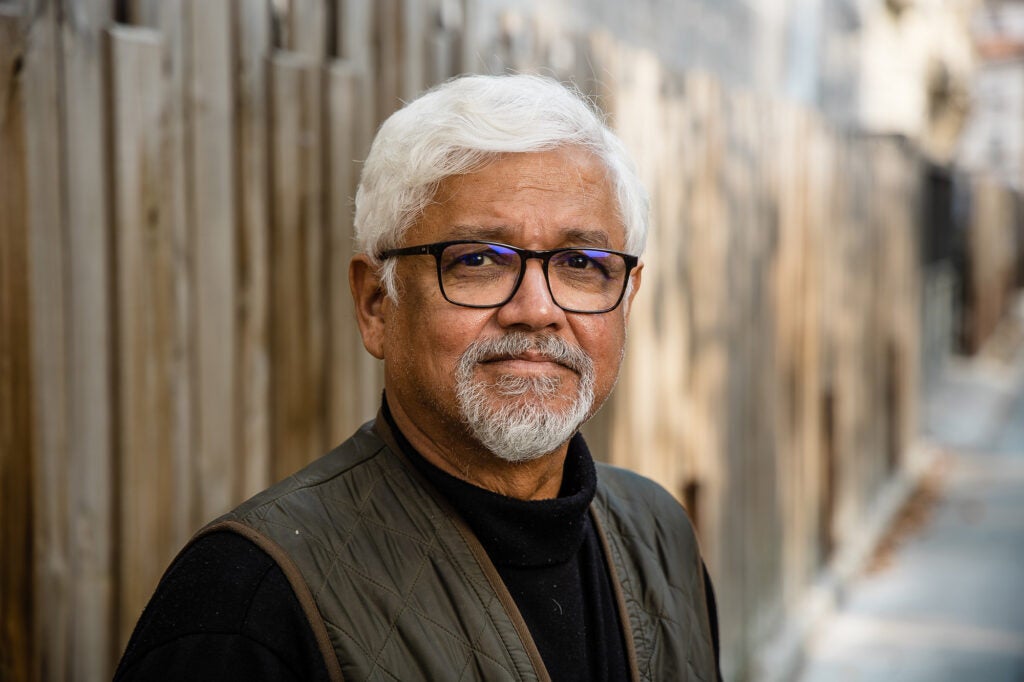

Amitav Ghosh

Amitav Ghosh is an Indian author and scholar whose fiction and non-fiction explore history, colonialism, and climate change. With works translated into over thirty languages, Ghosh has been recognized with numerous literary honors, including his election to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and his 2024 Erasmus Prize.

What do you feel is the role of literature/writing in the climate movement?

Literature has a unique power to humanize the climate crisis, to make it visceral and immediate. It can bridge the gap between abstract scientific data and the lived experiences of people. Stories allow us to imagine alternative futures, to empathize with those on the frontlines of climate change, and to confront the uncomfortable truths of our collective responsibility. Writing can also challenge the dominant narratives of progress and development that have brought us to this precipice. In this sense, literature is not just a mirror but a catalyst for change.

What advice do you have for students and/or young writers that want to tell climate stories?

My advice is to immerse yourself in the world—listen to the stories of those most affected by climate change, observe the natural world, and read widely across disciplines. Don’t be afraid to experiment with form and genre. Climate stories don’t have to be overtly didactic or apocalyptic; they can be subtle, personal, and even humorous. Most importantly, remember that storytelling is an act of hope. By telling these stories, you are contributing to a collective reimagining of our relationship with the planet.

If you distilled your work into one message, what would it be?

If I were to boil my work into one message, it would be this: The climate crisis is not just an environmental issue; it is a crisis of culture, imagination, and justice. To address it, we must fundamentally rethink our place in the world and our relationships with one another and with the Earth. Stories are essential to this transformation, for they remind us of our shared humanity and our interconnectedness with all life.

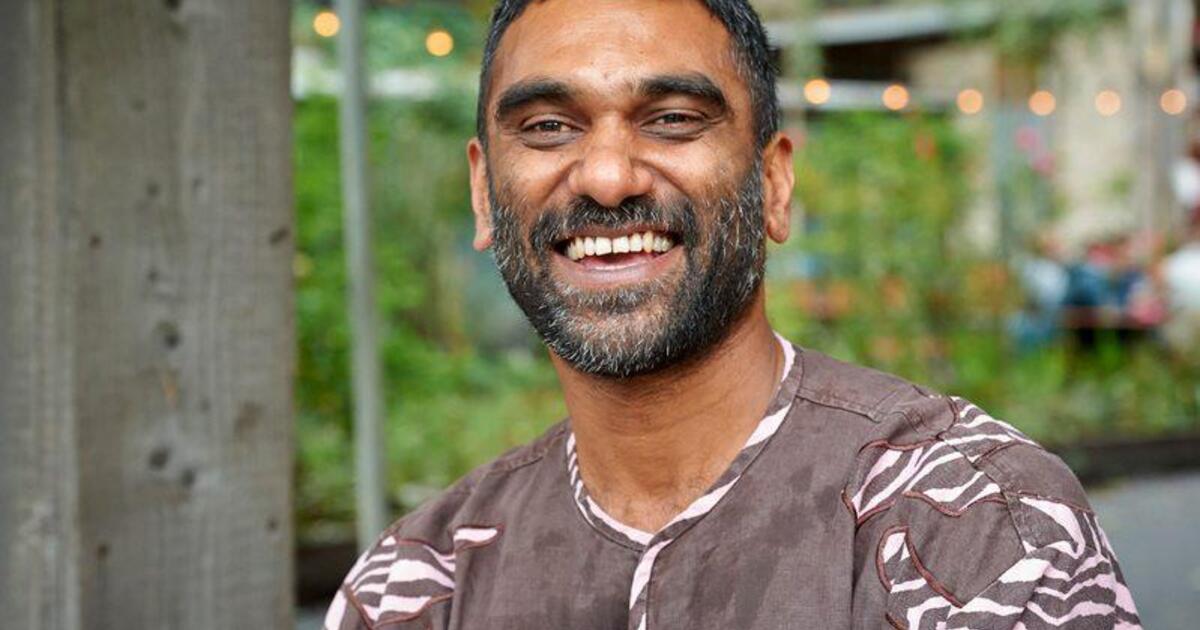

Kumi Naidoo

Dr. Kumi Naidoo is a human rights and environmental activist who has led a range of education, development, and social justice initiatives, the founding chair of Africans Rising, and previously held executive roles at Amnesty International, Greenpeace International, and CIVICUS.

What is your climate story? How did you come to this work?

My climate story is deeply rooted in my lived experiences growing up in South Africa during apartheid. I witnessed firsthand how systemic injustice and inequality devastate communities and ecosystems alike.

The fight for climate justice is, for me, an extension of the fight for human rights. I came to this work because I realized that the climate crisis is not just an environmental issue—it is a crisis of inequality, of power, and of humanity’s relationship with the planet.

It is the defining struggle of our time, and I could not stand by and watch.

What do you feel is the role of literature/writing in the climate movement?

Literature and writing have the power to humanize the climate crisis. They can translate complex scientific realities into stories that resonate emotionally and morally. Writing can bridge the gap between the head and the heart, inspiring action by making the crisis personal and urgent.

It can also amplify the voices of those most affected—communities on the frontlines of climate impacts—who are often excluded from mainstream narratives. In this way, literature is not just a tool for awareness but an invaluable tool for justice.

It allows us to connect the dots between systemic oppression and environmental destruction, and to call for transformative change.

Do not shy away from the hard truths, but also do not lose sight of hope.

Kumi Naidoo

What advice do you have for students and/or young writers that want to tell climate stories?

My advice is simple: write with courage and authenticity. Do not shy away from the hard truths, but also do not lose sight of hope.

Climate stories are not just about doom and gloom—they are about resilience, resistance, and the possibility of a better world. Listen to the voices of frontline communities, center their experiences, and use your writing to challenge power and privilege. And remember, your words have the power to move hearts and minds. Use that power wisely.