“Our findings highlight institutional and fisheries management concerns for their UN-mandate to ensure the long-term conservation of fish and associated ecosystems.” – Dr. Gabrielle Carmine

High Seas at Risk: Study Finds Global Fisheries Governance Lagging Behind What’s Possible

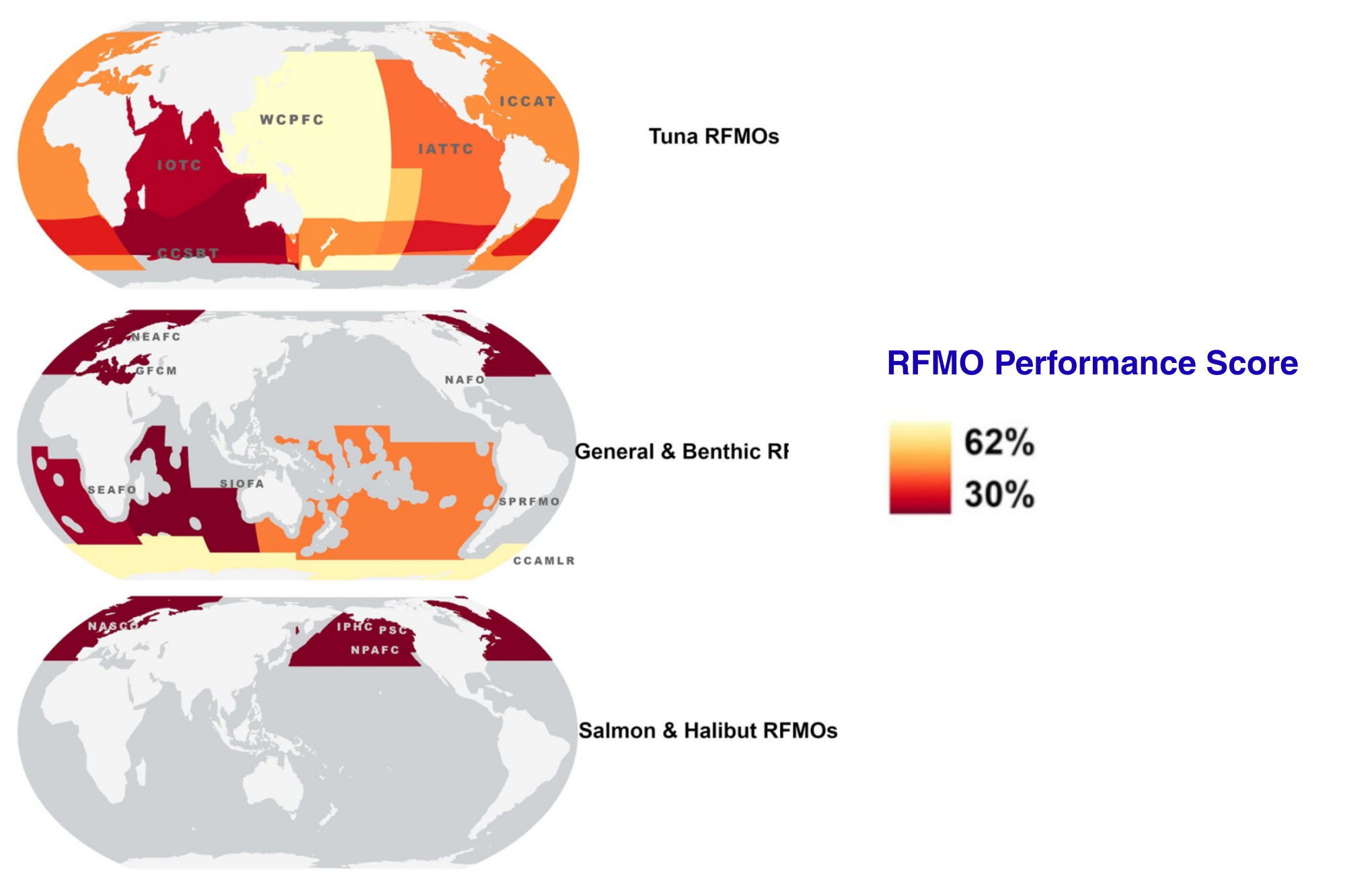

An evaluation of 16 Regional Fisheries Management Organizations shows significant underperformance across key management areas and discusses policy actions that could immediately improve stock and ecosystem health.

A new paper published in Environmental Research Letters led by Dr. Gabrielle Carmine, a Postdoctoral Fellow at Georgetown University’s Earth Commons Institute, offers an updated examination of how well the world’s Regional Fisheries Management Organizations (RFMOs) are meeting their dual-responsibility to ensure sustainable fishing and long-term conservation of fish on the high seas. The results show a system that is not functioning to meet its mandate, and while the gaps are substantial, the study also points to concrete fixes through the new UN Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction Treaty (UN BBNJ) that are within reach.

The study, “An expanded evaluation of global fisheries management organizations on the high seas,” published in Environmental Research Letters, brings together an interdisciplinary team of researchers from Georgetown, Duke, UMass Dartmouth, IUCN, and Stockholm Resilience Centre, and the University of Miami. The team examined 100 performance indicators across ten categories, including ones like catch limits, bycatch rules, transparency, compliance, and data reporting—to evaluate 16 RFMOs that oversee industrial fishing across nearly half of the Earth’s surface.

The outcome was sobering: the average RFMO scored 46 out of 100.

At least one RFMO received the full point for 90 out of 100 indicators, showing improvement is possible, but not widely obtained.

Read the paper“RFMOs have been critiqued for years, and unlike official RFMO performance reviews, this review is truly independent,” says Carmine. “Our findings highlight institutional and fisheries management concerns for their UN-mandate to ensure the long-term conservation of fish and associated ecosystems.”

A System Under Strain

The high seas—which comprise the two thirds of the ocean beyond any country’s jurisdiction—are one of the planet’s few global commons. In 2023, the adoption of the UN BBNJ agreement reflected a growing global desire to protect this enormous, ecologically vital region. But the day-to-day job of managing high seas fisheries still rests with RFMOs. Their UN mandate is clear: long-term conservation of marine fish populations, or “stocks,” and affiliated ecosystems, and ensure the sustainable use of fisheries.

Yet across 100 performance questions, the study found six indicators where every RFMO scored a zero. Only a few indicators saw all RFMOs earning the full point. And, most strikingly, the team found either no relationship between an RFMO’s management score and the status of the fish stocks in an RFMO’s convention area, or weak inverse relationships consistent with the last review 15 years ago.

RFMO policies are not having an impact on the fish they are charged to manage and conserve, indicating a potential institutional problem.

To understand the full picture, researchers paired their governance assessment with satellite-based fishing activity data and fish stock status plots from Sea Around Us. Five RFMO regions showed the highest concentration of industrial fishing effort. Across all 16 RFMOs, 56% of assessed target stocks were overexploited or collapsed.

“Similar to the last independent RFMO review 15 years ago, RFMOs with better policies didn’t have better management outcomes for their target stocks or fishing effort,” Carmine says. “We think this could be due to many reasons, one being that RFMOs are reactionary and are not engaging with a precautionary approach or that best-practice RFMO policies are obfuscating ineffective enforcement.”

“This study shows that the solutions aren’t mysterious or out of reach: we now have empirical evidence for which fisheries management techniques improve fish population status and reduce impacts.” – Dr. Carmine

A Blueprint for Immediate Improvement

Still, the findings are not simply diagnostic—they are instructive.

Across the system, a handful of policies showed clear associations with healthier fish stocks. These are not futuristic solutions; they already exist, just not widely enough. They include creating protected areas within RFMO boundaries; banning at-sea transshipment—a practice that can obscure illegal or unreported catches, allowing them to enter the seafood market—and reducing allowable catch limits when overfishing is detected.

The question is no longer whether better outcomes are possible, but whether countries will choose to scale the tools already proven to work.

Dr. Melissa Cronin

“This study shows that the solutions aren’t mysterious or out of reach: we now have empirical evidence for which fisheries management techniques improve fish population status and reduce impacts,” said second author Melissa Cronin, an Assistant Professor at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth. “The question is no longer whether better outcomes are possible, but whether countries will choose to scale the tools already proven to work.”

The team also developed two relative “best case” benchmarks by combining the highest-scoring category from each RFMO and all questions where an RFMO was awarded the full point. This idealized composite reached 76.5 and 90 out of 100, respectively— above the score of any single RFMO. The gap between current performance and this achievable benchmark is what the authors describe as a “competence gap.”

“While we updated RFMO best practice metrics that have been industry standard for years, we decided to create relative benchmarks to get ahead of any potential critiques on our performance review criteria being too stringent,” Carmine said. “We showed that RFMOs were capable of ‘passing’ in theory, but not one RFMO passed in our review—even when we grade on a curve.”

A Critical Moment for the High Seas

The timing of this study is not incidental. With COP 30 concluding and countries preparing for the implementation of the BBNJ Agreement, which becomes international law on January 17, 2026, global negotiations are turning toward how to coordinate conservation measures, spatial protections, and sustainable use in areas beyond national jurisdiction.

We are publishing this work at a moment when the UN and its regional bodies have the potential for real change.

Dr. Carmine

This paper lands as a grounding data point—an empirical baseline showing both what’s working and where governance is faltering.

“The role of RFMOs is in flux as the new BBNJ agreement requires reciprocal collaboration for high seas biodiversity conservation,” Carmine says. “BBNJ has the authority to create high seas protected areas and fill the long-term conservation gap that RFMOs have created. We are publishing this work at a moment when the UN and its regional bodies have the potential for real change.”

The authors note that high seas governance is inherently complex. Nations come to the table with different interests, enforcement is difficult over vast areas, and scientific data is uneven. Still, the most effective policies identified in the study are already being implemented in at least one RFMO somewhere in the world.

“Reimagining sustainable fisheries and high seas biodiversity conservation can and should happen in the next few years with new governance opportunities and RFMO reform,” say the authors.

About the Lead Author: Bridging Science, Governance, and Human Behavior

Dr. Gabrielle Carmine is a marine sustainability scientist whose work sits at the intersection of ecology, ocean conservation, and its governance through United Nations treaties and corporate accountability research. As a Postdoctoral Fellow at Georgetown University’s Earth Commons Institute, she studies global fisheries management, modeling the future of the high seas, and the political and social dynamics that shape biodiversity conservation outcomes in this vast environment.

Her research blends geospatial analysis, marine ecology, conservation, policy analysis, and oceans governance. Before coming to Georgetown, Carmine earned her Ph.D. at Duke University’s Nicholas School of the Environment in the Marine Geospatial Ecology Lab led by Dr. Patrick N. Halpin, where she focused on high seas governance, the geospatial behavior of industrial fishing fleets, the corporate actors behind this activity, and how their actions and lack of accountability may negatively impact conservation of high seas biodiversity.

Carmine’s work aims to illuminate not only where governance fails marine biodiversity, but how it can succeed—and what steps can be taken now to build a more sustainable, resilient future for the world’s largest shared ecosystem.

The Verge: Who owns the boats looting the high seas?