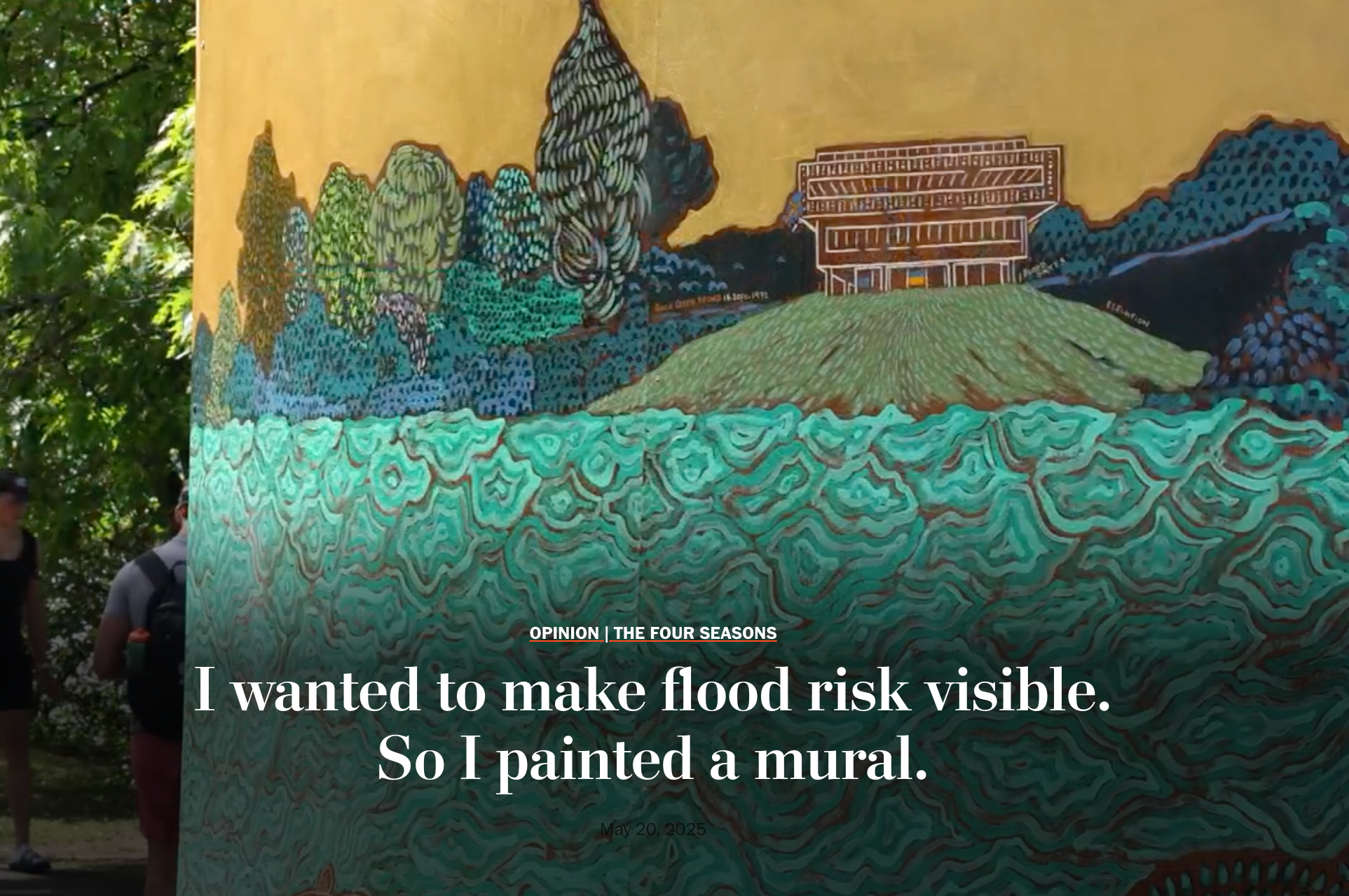

“A River Runs Through It” is a tribute to James Creek and the communities that have lived and thrived in its floodplain for centuries…I wanted the artwork to feel like a celebration of the entire Southwest quadrant of the city.

A River Runs Through It

Opinion from Andrea Limauro, Earth Commons Artist-in-Residence

A “ghost” creek that no one can see runs through Southwest DC.

Residents live, drive, and play on top of it and its vast floodplain. Even those who live in or near the buildings and landmarks named after it often don’t know about its existence. To see James Creek, one must know which manhole under which street to lift — because for over a hundred years, the creek has been buried in a dark brick tunnel. The brook that once poured from springs south of Capitol Hill gently flowed down as a tributary to the Anacostia River. It is now out of sight, and on dry days, it is a trickle more than a creek. However tiny, invisible, and seemingly trapped underground, this branch of the Anacostia River poses a risk for Southwest residents.

With intense precipitation and storms, “ghost” rivers, waterways that have been buried under human development, can reemerge from underground hiding and deluge the surrounding area.

The James Creek floodplain, the natural “breathing space” that waterbodies need to expand and contract with seasons, precipitation, and tides, now cuts through the fully built-out Buzzard Point peninsula and Southwest, increasing flood risk for thousands of residents.

A rich floodplain and a collapsing empire

Whereas indigenous people thrived in these floodplains rich in fishing, oysters and wild rice, with the establishment of the Capital in colonial times, James Creek began to be treated as a nuisance to be managed rather than a resource to be protected, effectively turning its lush floodplain to undesirable land over the next two centuries.

James Greenleaf, the land speculator who, by 1794, owned one third of the buildings for sale in Washington, DC—owned so much land south of the Capitol that for a while Buzzard Point itself was known as Greenleaf’s Point. The creek that runs through Greenleaf’s Point became known as James Creek after the same man. Today, he is also the namesake for the local recreation center and park, the marina and one of the older public housing communities. However, James Greenleaf’s real-estate empire collapsed before he could see the land of Greenleaf’s Point developed.

As the capital developed north of the White House instead of south of the Capitol building as some had speculated, Southwest and the Point became mostly dedicated to farmland. As the Washington Arsenal expanded on the peninsula’s tip and the Navy Yard next door, farms gave way for weapons testing. By the early 1900s, the creek increasingly became a dumping ground for waste, and industrial uses took over the southern portion of the peninsula. The land along the James Creek floodplain, thus, started to be viewed as less desirable than the rest of the Southwest quadrant. This became apparent in the planning decisions that followed the urban renewal project and resulted in the complete redevelopment of this quadrant of the city.

Urban renewal meets an invisible flood plain

The urban renewal project, the first-ever and to-date largest in the nation, leveled 99% of buildings in the Southwestern quadrant of the city and forced 4,500 African American families from their homes and businesses to make room for modern tower-in-the-park residences for the expanding federal workforce.

Over the following three decades, the planned redevelopment of the Southwest quadrant prioritized the development of luxury and market-rate housing, leaving the James Creek floodplain to be redeveloped last and with a concentration of public and affordable housing projects. One of the most durable legacies of urban renewal in Southwest is that today the James Creek floodplain is home to one thousand units of public housing across three communities. This concentration of vulnerable populations in this invisible floodplain creates disproportionate risk.

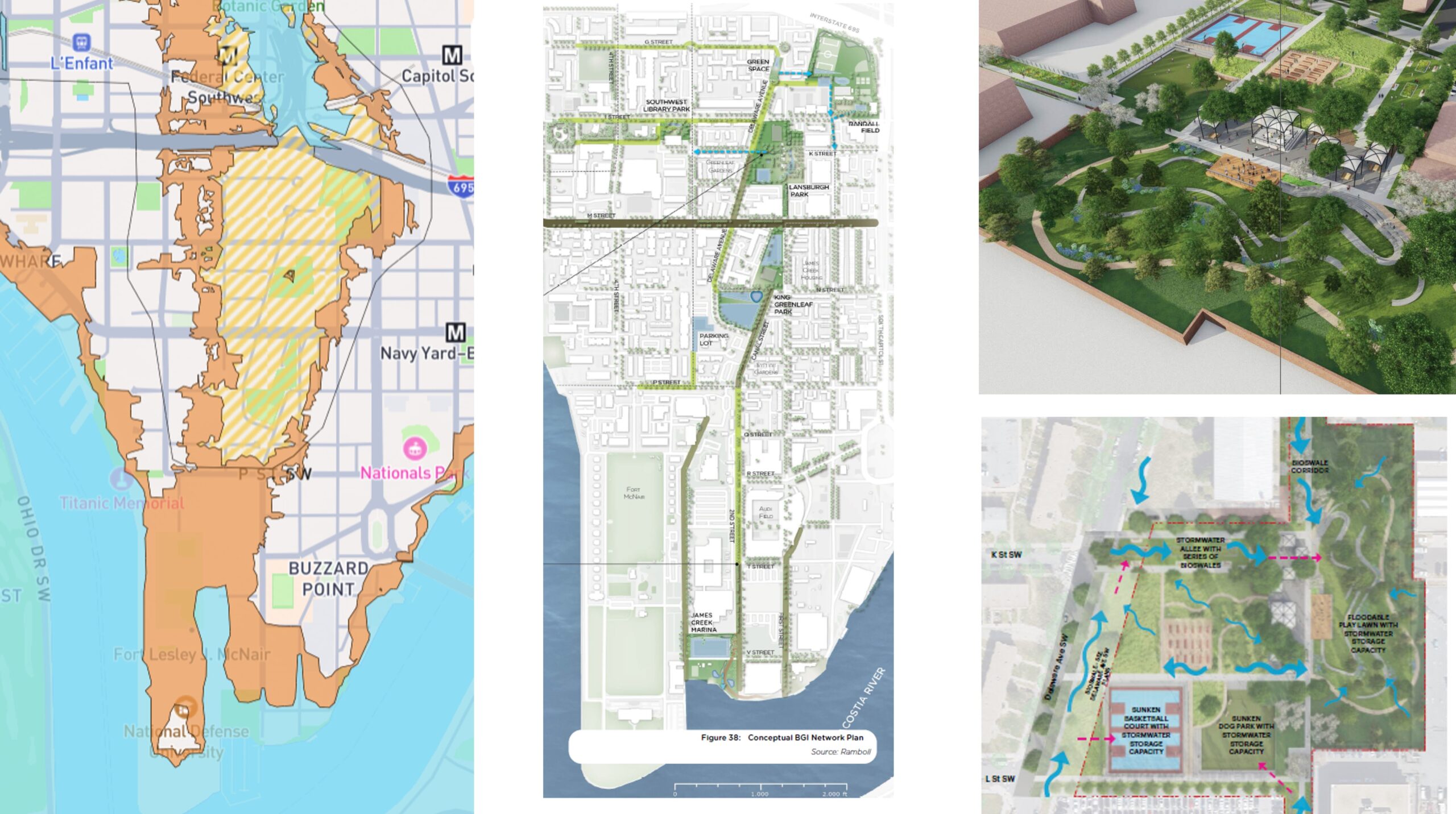

The urban renewal redevelopment approach set aside space for three parks—Randall, Lansburgh and King Greenleaf Parks—along the old creek’s route. This string of open spaces has created an opportunity for planners and residents to work together to rethink these spaces and the streets connecting them through the lens of water.

The District plans to increase the community’s resilience to flood risk by redesigning the three parks and the streets that connect them into a network of blue-green infrastructure and “sponge” parks, open spaces designed to purposely absorb and store large quantities of stormwater and floodwaters.

The added bonus of the design process was the opportunity to work with the community on updating the spaces to be more responsive to the communities’ recreational needs when the community is not flooding. This is most apparent in the re-design of a portion of Lansburgh Park, the main sponge park in the community-wide network, which will feature a large central bio-swale with a nature and public art trail around it, as well as an expanded stage area for hosting popular local events like community picnics and concerts.

The art of painting risk and resilience

While it will take a few years to fully implement the flood resilience plan, I decided to paint my latest mural, “A River Runs Through It,” in Lansburgh Park this past October. This mural is the third of my “A Climate of Future Past” series. As with my previous two climate murals—“The River and the Town” and “Endless Summer”—the location is significant, as it is symbolic both of risk and its solution. The third mural is painted over the longest wall in the park which runs parallel and over the buried James Creek and in front of the future sponge park. The wall’s location made it the perfect setting for a painting about the main climate risk for many communities in the fall: flooding from storms. “A River Runs Through It” is a tribute to James Creek and the communities that have lived and thrived in its floodplain for centuries.

End of carousel collection.

I had several goals for this mural.

The mural is painted along a 230’ long and 7’ tall brick wall that separates the future sponge park area of Lansburgh Park from the noise (and emissions) from the adjoining District of Columbia Motor Vehicle Inspection Station. First, I had to figure out how to organize and compose the artwork on a wall so long and skinny.

End of carousel collection.

I used the long L-shape of the wall, as well as its direction perfectly aligning with the shape of the peninsula, to design a landscape of the Southwest quadrant from the National Mall and the Tidal Basin, through the Federal Rectangle, Southwest and ending on the Buzzard Point.

End of carousel collection.

I wanted the artwork to feel like a celebration of the entire Southwest quadrant of the city. For this, I selected about three dozen landmarks, buildings and historical figures that have left a mark on the area. These include a mix of national monuments and buildings as well as landmarks with more local significance.

End of carousel collection.

I also wanted the artwork to speak to flood risk and flood resilience, so the mural depicts the peninsula during a storm that revives James Creek and floods the floodplain and Lansburgh Park.

The final goal for the artwork was to make the park feel more welcoming, large and open. Lansburgh Park was designed to be surrounded by buildings, light industrial uses and walls, making the center of the park, where the “sponge” feature will be built, feel very enclosed and walled in. By painting plant forms, organic shapes, and colors, I created the illusion of the park extending beyond the wall. Now, the longest wall in the park blends into the rest of the landscape and makes the park feel bigger and more open.

End of carousel collection.

I decided to paint the mural with the assistance of volunteers from the community.

I wanted this to honor and recognize the long tradition of civic organizing in Southwest that is also a legacy of the urban renewal plan.

To complete “A River Runs Through It,” I worked with the local non-profit Good Projects and the Southwest Business Improvement District (SWBID) to recruit student and resident volunteers. It took about 50 hours of painting outside over 6 days for 25 residents, the parks’ urban farmers, local high schoolers from Richard Wright High School, and staff from the SWBID and the Department of Parks and Recreation, and me to complete it.

The dedication, time, and effort that residents and students put into the mural, the pride with which they created art for their neighbors, and the community that was created through the project are all reminders of the importance of building up a community’s social capital. The social networks that support the growth and resilience of a community is an important but often forgotten piece of the climate resilience puzzle. At a time when extreme individualism reigns, it is a good reminder that individual resilience is often only possible within a resilient community.

“A River Runs Through It” is the third of four murals I’m creating for my year-long “Climate of Future Past” public art and climate engagement project. This project was initially commissioned by The Washington Post Opinions until it was abruptly canceled just days before the beginning of this third mural. Despite the cancellation, I have resolved to complete the last two murals and write the accompanying two opinions—this piece you are reading being the first of the two—that would have been published in the newspaper before the rescinded support for the project as part of its recent editorial “re-alignment”.

“A River Runs Through It” was made possible with the generous support of the SW Business Improvement District. Other supporters include the DC Department of Parks and Recreation, Good Projects, Richard Wright Highschool and students, the Lansburgh Parks Farmers. The Earth Commons is supporting Andrea’s Climate of Future Past through a year-long Artist in Residence fellowship which the artist used to create the first artwork: The River and the Town.