My art piece wants to be a library of knowledge of things that we are losing. We are losing databases. We are losing diversity stories in our museums. Exhibitions are being censored. Students and professors are being censored.

Climate in the Public Eye: How the Earth Commons Artist-in-Residence is Continuing the Conversation on Climate Resilience

Earth Commons Artist-in-Residence Andrea Limauro’s public art series, “The Climate of Future Past,” uses seasonal installations to highlight climate risks in D.C. The first piece, now completed on the Georgetown Waterfront, explores Potomac River flooding and invites public reflection on resilience, history, and care.

Cascading jewel tones and fantastical geometric shapes forming a hint of landscape catch your eye when you see Andrea Limauro’s work on walls around D.C.—and, most recently, on the Georgetown Waterfront.

His newest work is the first of a four-piece series titled “The Climate of Future Past”, which was commissioned by the Washington Post and supported by the Earth Commons’ (ECo) artist-in-residence program. “The Climate of Future Past,” is meant to raise awareness about the climate risks associated with each season in four different communities in the nation’s capital through four public artworks and accompanying opinion pieces for the Washington Post, coinciding with the start of each of the four seasons. The series name itself derives from the fact that in 2024, the world surpassed a key warming threshold of 1.5 degrees celsius above the 1850-1900 pre-industrial average for the entire twelve-month period of February 2023-January 2024. Scientists have long urged that limiting warming to below 1.5 degrees Celsius would “significantly reduce the risks, adverse impacts, and related losses and damages from climate change.” As Limauro puts it, “We now live in the ‘Climate of Future Past: the climate that in the past we promised would not be our future but is now our present.’”

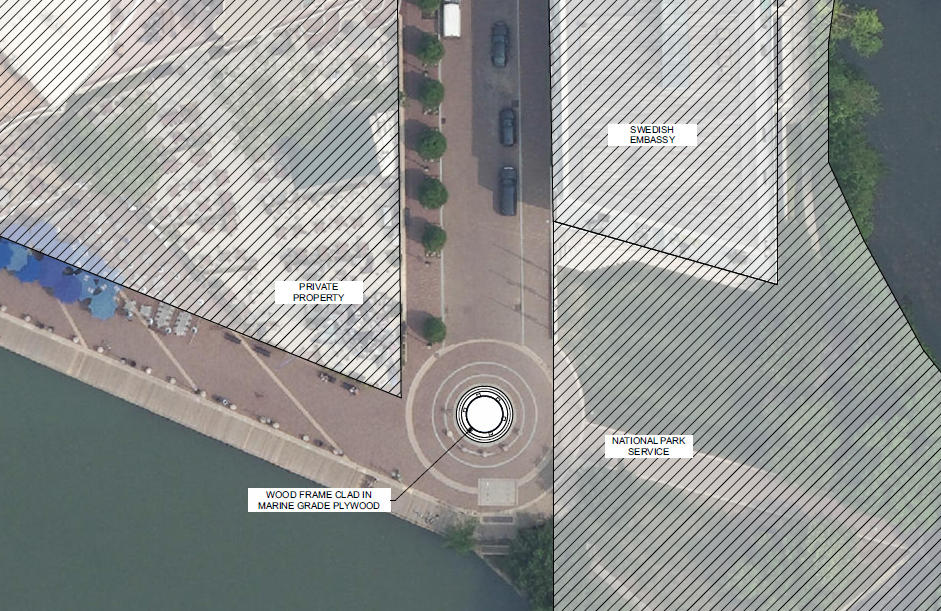

The first of the four pieces, “The River and the Town,” which examines the risk of the Potomac flooding in Spring, will reside on the Georgetown Waterfront until October 2025, when it will be moved permanently to Georgetown’s campus. To come are pieces on urban heat in NoMa, the neighborhood north of Massachusetts Avenue, for the summer; storm surge flooding in Anacostia for the fall; and, environmental stewardship and resilience at the Hirshhorn Museum on the National Mall for the final winter work.

As the first piece on the Waterfront nears completion, the context behind the piece and the public reaction demonstrate the impacts of the artist-in-residence program.

Limauro chose to build “The River and the Town” installation in place to facilitate conversations with passersby. This is part of an intentional move by Limauro to bring more of his work into the public eye. While art has been a go-to passion since childhood, Limauro did not pursue art professionally until the late 2010s, when he submitted a few of his pieces for an open-call art show at a downtown gallery in DC. Even now, Limauro continues to work in city planning, where he turns the sustainability and resiliency themes from his art towards reshaping city infrastructure and policies to better meet the community’s needs.

End of carousel collection.

After selling all but one of his paintings at that art show on the first night, he began pursuing art more intensively, selling work to galleries and private collectors. This didn’t fully satisfy Limauro, who considers much of his work political and therefore belonging in the public eye, where it can engage in the political conversation. He began seeking to “democratize” his art by embracing murals and public art; a goal the artist-in-residence fellowship has allowed him to continue to pursue this year by supporting his creation of four pieces for the public.

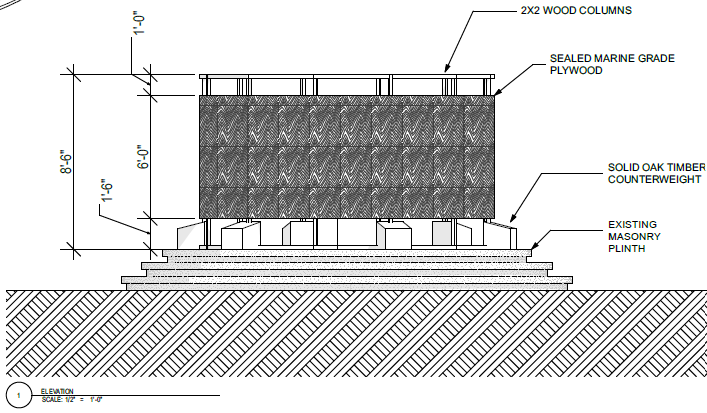

Limauro’s tactic to engage the public seems to be working. Over the weeks that Limauro has spent constructing the piece, people have paused to chat with the artist about what is taking place. Little do they know that a second tactic is at play. Their eyes, first drawn to the fantastical colors and imagery, suddenly alight on familiar structures from the D.C. skyscape: the Washington Monument, the Cathedral, the Watergate building, among others. Observers lean in and ask what exactly they are looking at. The answer: the high water mark of the Potomac under flood conditions.

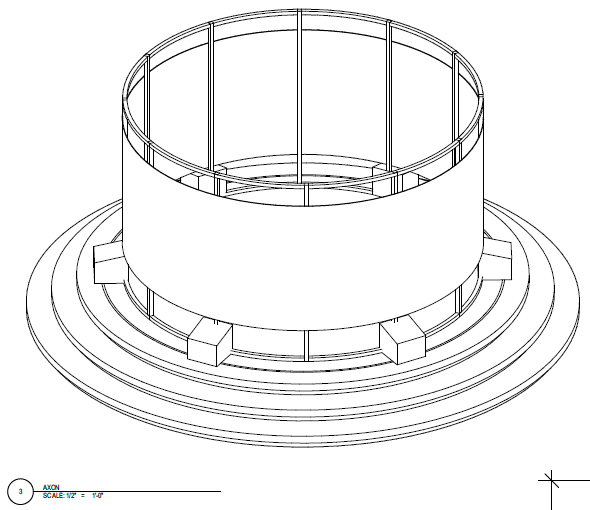

The piece is circular in form, and as one walks around its circumference, it acts as a mirror, reflecting what is directly behind the viewer’s back under flood conditions. The familiar buildings and geographies are really a collection of resilience stories throughout the Potomac floodplain that weave past, present and future: on Roosevelt Island, for instance, Limauro included the story of the 1st Regiment of United States Colored Troops (USCT) that fought in the Civil War, and which had to be escorted out of D.C. for training on the island to prevent violence from white mobs in the capital.

End of carousel collection.

As “The Climate of Future Past” emerges in our current political moment, the collection of resiliency stories takes on new meaning. ”The context is changing the work,” reflects Limauro. “It’s making it a lot more relevant. My art piece wants to be a library of knowledge of things that we are losing. We are losing databases. We are losing diversity stories in our museums. Exhibitions are being censored. Students and professors are being censored. I am going to write the climate-related flood predictions into the piece.”

The political era in which the pieces are debuting is also already shaping the public response to “The River and the Town.” Limauro says that one of the most common responses from those conversing with the artist as he paints has been, “Thank you.” He explains, “I think people are a little scared right now and seeing an artist in the capital doing this work and having these conversations very openly gives them some hope that there are people willing to challenge the current narrative about climate and the environment and, also, generally about care.”

My art piece wants to be a library of knowledge of things that we are losing. We are losing databases. We are losing diversity stories in our museums. Exhibitions are being censored. Students and professors are being censored.

To Limauro, care above all is the intent behind the first piece. “It is so important at this time for people to rediscover the beauty of caring. Caring for people, caring for art, caring for the environment. Just caring. We are confronted by a culture that is telling us not to care about anything and I think that, as artists, we should care more.”

Limauro embodies caring not only in the intentional design of the piece but also in the materials he utilized. For instance, the frame of the exhibition was crafted from the wood of ash trees that died from ash bore disease or fell in recent storms in a forest about 20 miles upriver in Maryland. In preparation for the project, he teamed up with local architecture and design firm To Be Done Studio to steam and bend the wood to the proper form.

End of carousel collection.

As Limauro wraps up the installation of “The River and the Town,” he is excited to begin the next phase of public engagement with the piece: bringing the Georgetown University community into the conversation, especially students.

“What is really important about the residency is that it gives me the opportunity to engage and have those conversations with the future professionals who are going to pick up my work where I leave it in a decade or so. Inspiring the people who are going to keep doing the work—and hopefully better than I have—it couldn’t be more important.”

End of carousel collection.

In addition to an opening celebration at the Swedish embassy (date forthcoming), Limauro will be leading artist and resilience planning walks exploring his art and climate resilience infrastructure in the city over the next year.

What is really important about the residency is that it gives me the opportunity to engage and have those conversations with the future professionals who are going to pick up my work where I leave it in a decade or so.

Andrea Limaruo, Earth Commons Artist-in-Residence

Whether it is in a formal tour setting or not, be sure to see Limauro’s work on the Waterfront; and more than that, strike up a conversation about the world we are living in and how we can show it and us all, a little more care.